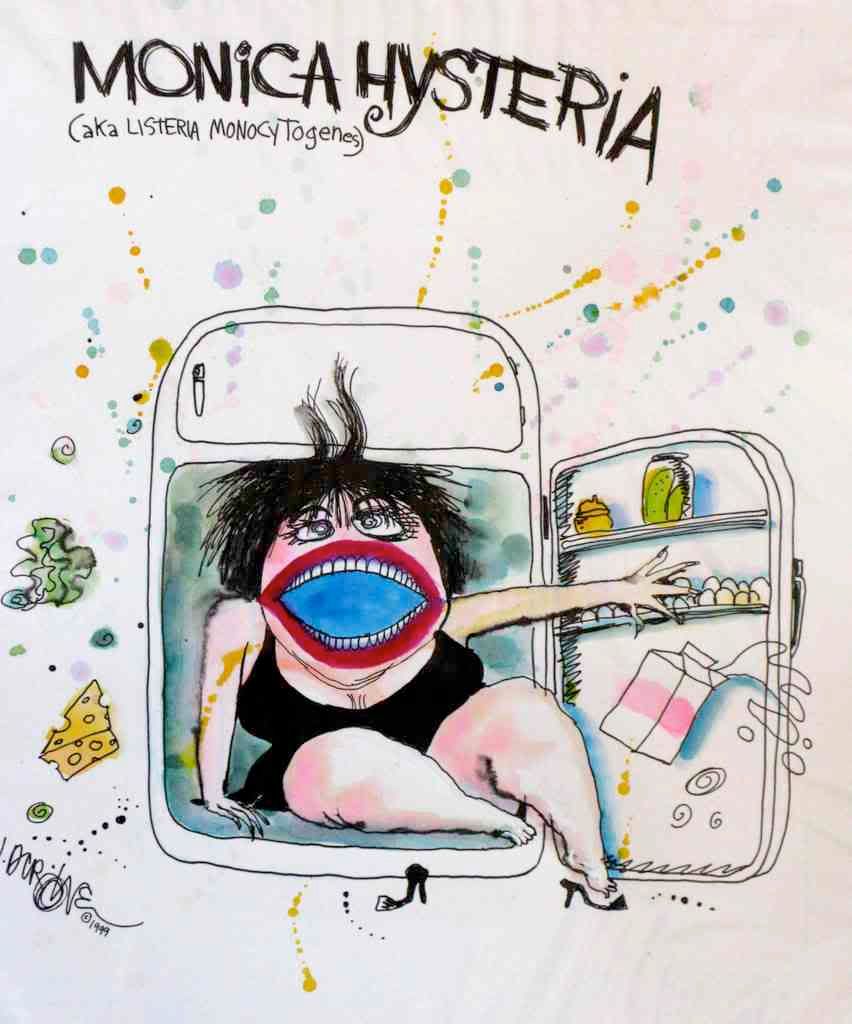

Listeria monocytogenes, an old friend which appears to have taken a nap in North America, has been staging a comeback in Europe.

Listeria monocytogenes, an old friend which appears to have taken a nap in North America, has been staging a comeback in Europe.Dr. Véronique Goulet sounded the alarm in an article published this past week in the "Bulletin épidémiologique hebdomadaire" (Weekly Epidemiological Bulletin). The English abstract of the article reads:

From 1987 through 2001, the incidence of listeriosis in France declined spectacularly, then stabilised until 2005 to around 3.5 cases/million inhabitants. This trend changed suddenly in 2006 with an incidence increase of 4.6 cases/million inhabitants, which continued until 2007 to reach 5.0 cases/million inhabitants. This increase has occurred mainly among persons >60 years of age and immunosuppressive patients, regardless of their age. No increase has occurred in pregnancy-associated cases. Most geographical districts are involved, and seasonal variation is similar than before 2006. The increase of incidence is not linked to the emergence of particular strains at the origin of clusters, and the increase occurred in both sporadic and cluster-associated cases. In nine other European countries, an increase of listeriosis has also been observed during the period 2000-2006, with similar characteristics as in France (occurring in subjects >60 years, with no geographical and temporal clustering, and no emergence of any particular strain). In France, as in other European countries, the cause of this increase remains unknown. Different hypotheses contributing to explain this increase are discussed here.

According to an article published in Le Monde this past week, Dr. Goulet has proposed a few possible explanations for the sharp increase in incidence of Listeria monocytogenes infections:

- Reduced salt levels in many processed foods in response to government attempts to reduce the salt intake of the population;

- Increased popularity of raw foods, such as sushi; or

- Extended shelf-life of many refrigerated foods, which would allow low levels of Listeria monocytogenes to multiply.

Modified atmosphere packaging – replacing all or part of the oxygen in a sealed package with another gas – is an effective way to extend the shelf life of many perishable products. The technology is very successful at suppressing spoilage bacteria, most of which grow only in the presence of oxygen. But food-borne pathogens grow even in the absence of oxygen. Some of them – including Listeria monocytogenes – prefer an oxygen-poor environment.

USDA researchers have been studying the effect of modified atmosphere packaging of produce on bacterial survival and virulence. They found that bacteria grown under modified atmosphere became better able to survive stomach acid. The phenomenon was especially noticeable when packages of produce were held at "abusive" storage temperatures (room temperature or warmer).

Recently, the UK Food Standards Authority recommended that vacuum packaged foods and foods packed under modified atmosphere be limited to a 10-day shelf life. The regulators issued this guideline in order to minimize the risk that Clostridium botulinum might grow in the packaged products. But the 10-day limit should also reduce the risk of Listeria monocytogenes, which grows even more happily at refrigerator temperatures than C. botulinum.

The French have initiated a new survey this year to determine the level of Listeria monocytogenes contamination in various ready-to-eat foods. Dr. Goulet hopes that the results of this survey will help to explain the increased incidence of listeriosis in Europe. And point to a strategy to reverse the trend of the past few years.

If Western Europe is experiencing a large increase in listeriosis, can the United States and Canada be far behind? A quick look at a CDC surveillance chart shows that the incidence of Listeria monocytogenes reported to FoodNet dropped nearly in half between 1996 and 2002, then rose by almost 50%, and has remained in a fairly stable range since then. In 2007, the reported incidence of lab-confirmed cases in the United States was 2.7 per million population – a bit more than half the 2007 incidence in France. It's anybody's guess what will happen in 2008.

What can consumers do to reduce the risk of contracting an infection with Listeria monocytogenes? Here are some suggestions:

1. Buy unwrapped, unwashed produce.And pay attention to the next recall announcement.

2. Avoid buying packaged ready-to-eat food that is nearing its "sell by" date.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.